Without having to investigate the most distant history, which has however left important traces on the territory – just think of the first Etruscan settlements, of which the "Lago degli Idoli" is the most important archaeological site of our Apennines, or, in medieval times, the roads travelled by pilgrims - especially Germans - who crossed the ridge to the Serra Pass, to the Casentino, and then to Rome - we can still say that a fair part of the park territory has been subjected to long-term unitary management, which was probably fortunate for our forests. After the feudal era, with some large families like the Guidi and the presence of strong religious and administrative entities such as the one of Camaldoli, following the many historical events that shocked the whole of Italy it was the turn of the Florentine dominion, the Republic, and the Lordship that managed in a farsighted way, through the secular Opera del Duomo of Florence, up to the era of the grand-dukes and the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy, during which also the Romagna side of the park continued to be part of Tuscany. In the holy centuries, this strip of the Apennines (Ellero, Romualdo, Francesco and Pier Damiani made it their place of meditation) struck and impressed writers, painters, and artists in general. Among the most illustrious visitors of the park there is certainly Dante, who was particularly impressed by the waterfall f Acquacheta, that he celebrated in a canto of his Inferno. In the modern era, Dino Campana, an original voice in the poetry of the 1900s, recounted in his "Orphic Songs" his journey on foot from Marradi to La Verna. There were also many painters (from Mazzuoli and Fedi, authors of splendid eighteenth-century views, to Marchini and Lega, up to some illustrious contemporary artists) who portrayed our forests, as well as foreign travellers who, in times when the journey was considered an essential experience of life, fell in love with the Casentino area and its artistic and historical riches, the forests and hermitages that are embedded in it, and the majesty of the landscape.

Rediscovery of the history and culture of Romagna and Tuscany

The literary, artistic, architectural, and material testimonies of the civilization of this territory are a great wealth, as well as the biodiversity in other areas. Despite the age-old problem of practicability between Romagna and Tuscany and the marginality of the area, over the centuries this Apennine stretch has always been an important point of contact between different cultural areas, which would encounter here using the natural passes that cut the Apennine ridge. Therefore, historically the commercial, and cultural exchanges were strong, also in consideration of the fact that Romagna has been part, from an administrative point of view, of Tuscany for almost 500 years. It should be remembered that, from the mid-fifteenth century until the beginning of the Fascist Regime, the upper-middle part of the Romagna valleys, with the exception of the Montone valley which actually reached the gates of Forlì, belonged administratively to Tuscany, with obvious consequences on the culture, language, art, cooking and even to the dialect of these border lands. This corner of Romagna, which the grand-dukes themselves called precisely Tuscan Romagna, perhaps not feeling them to be like other parts of the Grand Duchy, for a very long period had special relationships with Tuscany, despite there being a natural barrier between the two lands, including Apennine ridge. These relationships were somewhat reduced during the twentieth century, and the park probably also had the merit of rediscovering these cultural bonds, with common origins but different characteristics, that were being lost and to restore administrative unity to the two territories.

Material culture

The territory is filled with signs of human presence, ranging from elements of artistic and monumental interest to handicrafts or objects of simple everyday use. All these signs, in one way or another, tell us about a lost world and culture, but this doesn’t mean they are dead or worth being forgotten. In short, the presence of a village, of a simple farmhouse, of a factory are the concrete evidence of the relationship that mankind had established with the territory and with nature. Moreover, among the

purposes of the protected areas there is also the preservation of archaeological, historical and architectural values, to integrate man and the natural environment, which is particularly valid in a territory like the one of the Park, where the bond between mankind and nature has very ancient origins and went on until a few decades ago without great differences from life in the distant past. From this point of view, one understands the value, for example, of ancient artefacts, such as bridges, majesties, and so on, and the importance of their recovery, since they not only make the territory more accessible and beautiful, but they also tell us about a way of life within nature and with nature that represents a great cultural treasure that needs to be safeguarded.

Religion and the environment

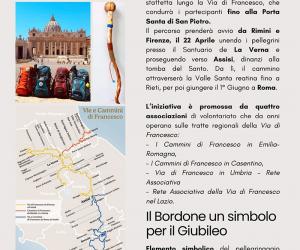

The park includes two places that are extraordinarily important and fascinating from a spiritual and historical point of view: the Hermitage of Camaldoli, founded in 1012 by San Romualdo, who chose this splendid place surrounded by thick fir-woods as a place of retreat and meditation , recognizing the importance of the care of the woods to such an extent to make it become part of the rules of the order; the Sanctuary of La Verna, built on the mountain that Saint Francis received as a gift in 1213 to make it a hermitage site, which dominates impressive crevices and rocky cliffs on one side and, on the other, is protected by the centuries-old forest of fir and beech trees, preserved intact for almost eight centuries by the Franciscans. The presence of these communities undoubtedly enriches our park, making it unique in the national scene and physically witnessing how man can live in harmony with nature.

Integra Solutions

Integra Solutions